Unliked value-based methods, policy optimization methods search over policy parameters without computing structured value representations for states (or state-action pairs), in order to find parameters that maximize (or minimize) a policy objective function.

Let

- Initialize policy parameters

- Sample trajectories

- Compute gradient vector

- Apply a gradient ascent update

In comparison to value-based methods, policy-based methods are

-

more effective in high-dimensional + continuous action spaces Value-based methods should generally select optimal actions based on something like

-

better at learning stochastic policies Policy-based methods are naturally stochastic: this is because our policy parameters

Why is stochasticity a good thing?

- exploration is optimal to train any policy

- in partial-observability settings/environments, deterministic mappings aren’t the only optimal solution

Evolutionary Methods for Policy Search

These are called evolutionary methods because they closely follow the evolution of a population!

- Initialize a population of parameter vectors Genotypes

- Make random permutations to each parameter vector Simulate mutations in offspring

- Evaluate the perturbed parameter vector

- Update your policy parameters to move to favor the best performing parameter vectors Survival of the fittest enabling fitness in this offspring

These are examples of black-box policy optimization, where we treat the policy and environment as a “black box” that we can query (run rollouts) and update our policy based purely on performance we can observe;

- we do not learned a structured “state” representation of state values and/or state-action values based on the structure of Bellman equations

- use gradients to update policy parameters directly like in policy gradient methods, but may do so indirectly like in NES

CEM: Cross-Entropy Method

In this method, we

- sample

- Evaluate those

- select a proportion

- use their corresponding

This worked really well up to the 2010’s and in low dimensional search space dimensions, shown to work well in Tetris (Szita, 2006), where we can craft a state-value function that is a linear combination of 22 basis functions

These evolutionary search methods weren’t a threat to DQN implementations at the time because they couldn’t scale to large non-linear neural nets with thousands of parameters.

CMA-ES: Covariance Matrix Adaptation

Instead of limiting ourselves to diagonal Gaussian, we search by learning a full covariance matrix so instead of just updating the mean and variances, we’re updating the full covariance matrix.

Visually, if there is an objective function we are trying to reach that is best maximized with samples in a 2d rotated ellipse, then we should utilize all the entries in a full covariance matrix which then allows us to rotate a standard diagonal gaussian matrix (x-y aligned ellipse) to best maximize this objective function efficiently.

NES - Natural Evolutionary Strategies

NES considers every offspring when updating our policy parameters - they optimize our expected fitness objective by updating the parameters of our search distribution through a natural gradient, specifically updating our learned mean

Consider the parameters of our policy

Our goal is find the best possible policy distribution, parameterized by

based on a fitness score which is the expectation of reward over entire trajectories

Deriving the Natural Gradient

Computing the update for our mean

From this derivation, we have shown that this gradient can be estimated by

- sampling

- Then we simply need to scale by a sampled noise term

To expand on that last step, in order to back propagate through Gaussian distributions to

Based on this derivation we can now apply gradient ascent to iteratively update our

Black-Box Optimization

To clarify, this is still black-box optimization:

- We do not need to know anything about how we are computing our fitness score, we are simply using raw output returns given our samples

- We are not computing computing analytic gradients of

Scalability + Parallelization of ES

The reason why this scales well for large dimension

- Coordinator broadcasts

- Coordinator sends

- Each workers runs trajectories and sends back

Because of reparameterization only this

Local Maxima Issue

In order to prevent ES methods from getting stuck in local optima, we average our search over multiple tasks and related environments to improve robustness and our objective can become more more generalizable.

Policy Gradient

We no longer consider black-box optimization methods. Instead of updating a search distribution that our policy parameters are sampled from, we directly update our policy parameters, because we need to compute analytic gradients directly!

Policy Objective

One reasonable policy objective is to maximize our expected trajectory reward over distribution of all trajectories parametrized by our policy parameters

Remember that

- the initial state being sampled from an initial state distribution

- the stochasticity of the policy in which actions are sampled from - this is what our

- the dynamics of the environment resulting in stochastic next states

It’s assumed that

We now need to figure out how to compute this gradient in order to find optimal

Finite-Difference Methods

One way to try and approximate policy gradient of

This was used to train these AIBO robots to walk. But this is really not feasible in high dimensions

Derivatives of the Policy Objective

Policy gradients aim to exploit our factorization of

In comparison to evolutionary methods, here the challenge is to compute derivatives w.r.t variables that parameterize a distribution that our expectation is summed over. The derivation uses the same log probability trick as derived for evolutionary methods; also we assume discrete trajectory space to sum over - if continuous, the derivation is largely the same but the justification for moving gradients inside the integral terms is different and above my math knowledge.

I think this part is intuitively explainable, our policy objective gradient is equivalent to increasing the log probability of trajectories that give a positive reward and decreasing the log probability of trajectories that give a negative reward.

The key observation is that this expectation can be simplified much further because our trajectories do encapsulate the dynamics of the environment - but this is not specifically parametrized by our policy parameters, so the derivatives of our trajectories propagate to derivatives of taking actions under our policy.

Then completing our derivation

To approximate the gradient, we use an empirical estimate to from

Computing Policy Gradient

And the natural question is whether the derivative term is computable - which yes it is.

- If our action space is continuous, then we our policy network can be gaussian, outputting a mean and standard deviation.

- If our action space is discrete, obviously we apply a final softmax layer to output a discrete probability distribution over finite action space. Then for stochasticity, we can query a categorial distribution based on these probabilities for sampling.

Temporal Structures

Can we do better than a standard

Instead, we should emphasize causality: Only future rewards should be attributed to the action taken at timestep

REINFORCE - Monte Carlo Policy Gradient

The above discussion concludes REINFORCE - the simplest policy gradient also referred to as “vanilla” policy gradient.

- Initialize policy parameters

- Sample trajectories

- Compute gradient vector

- Perform Gradient Ascent:

Baselines with Advantages

Our gradient estimator is unbiased, but still can have high variance

One issue with weighting our gradient updates with

- a state

- a state

To counteract this we should then only consider the trajectory reward above our a constant-term baseline - Advantages - at that state!

Actually, this new

And our subtraction of baseline to consider relative reward has effectively reduce the scale of gradient updates quite a bit, thus we minimize variance overall!

Baseline Choices

- Constant Baselines using the average return of the policy

- Time-dependent Baselines

- State-dependent Baselines i.e. value function

Actor-Critic Methods

Actor-Critic methods build of our state-dependent baselines used in REINFORCE with baselines method where our action advantage is

Our returns

Then our action advantages can be simplified as

- Initialize actor policy parameters

- Sample trajectories

- Calculate value functions

- Compute action advantages

In some sense the actor-critic is just “policy iteration” written in gradient form.

- We run the policy and collect a series of

- Based on the performance, we compute advantages for each time step during each trajectory

- Then we update our policy parameters directly using a policy gradient that is computed through these advantages.

A2C - Advantage Actor-Critic

The trajectories we collect arrive sequentially, while stability of training our policy networks require the gradient updates to be decorrelated - a problem we fixed in Q-learning using replay buffers - a solution is A3C by parallelizing the experience collection to multiple agents in order to stabilize training.

Workers run in parallel, computing gradients from their own rollouts, but we batch updates after each worker has finished their process to a combined gradient update step - ensuring consistent /stable gradient updates.

A3C - Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic

The natural performance optimization to make is what if the workers worked asynchronously and computed + provided gradient updates without waiting for all workers each iteration.

PPO - Proximal Policy Optimization

PPO is derived from policy improvement logic and more so a approximate policy iteration method than a policy gradient method.

High UTD

Obviously it seems to us that a high UTD is efficient with collected data - and a bottleneck in RL for complex environments is exactly data collection - so we want to come up with methods that work well with high UTD.

Here’s the issue:

if we apply one gradient update step, then we land on a new policy

This means that forcing a high UTD is a noisy estimate based on limited experience and can result in policy drifts. This is a motivator for PPO and TRPO methods as we discuss, which aim to fix this issue through

Policy Improvement

Performance of Policy

If we quantify the performance of a policy as expected return over all trajectory

and define a discounted state visitation distribution that weights time spent in a specific state

where

- the sum of all pmfs for

- the discounted average of some state-dependent function

Performance Difference Lemma

Then we can show that the policy improvement from

Policy Improvement Formulation

We aim to find the maximum new policy

Importance Sampling

But our whole goal for performance is to not sample from

which works as long as the denominator isn’t

Derivation

Then to apply this trick to our formulation, we aim to express our expectation entirely in terms of

but calculating state-visitation ratio

PPO fixes this by simply keeping

Now, to compute this objective max function, we need to take gradient ascent steps wrt to this object, and rewrite in the same policy gradient form

But we still have this issue of need to have a high UTD and resulting in policy drift. PPO aims to enforce some closeness penalty constraints on how far the new policy

Clipped Ratio Objectives

What PPO does is use a soft approximation by utilizing ratio clipping keeping the

This can be expressed as

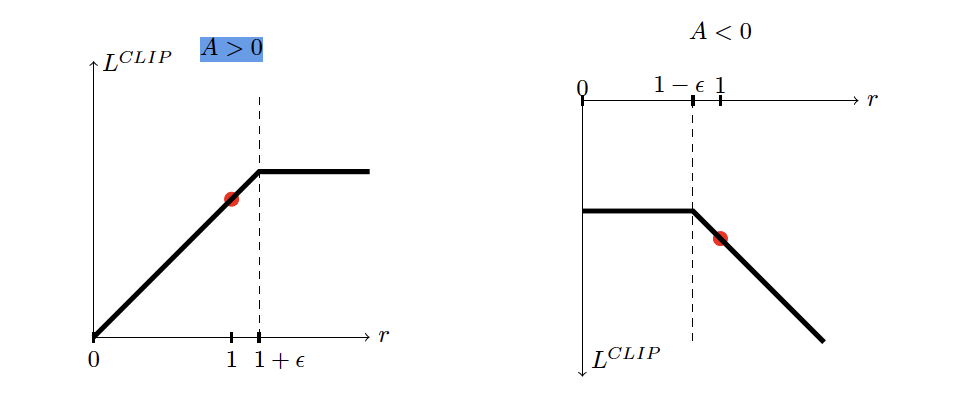

Note that a naive clip objectives clips our ratio on both sides of the curve. But this has the issue of

- if our advantage

- If our advantage

Then our entire clipped objective adds a min term so that we only flattens the ratio on the side we care about!

Asymmetric clipping

In reality we need to emphasize good actions when exploring for language models, meaning our clip term should be something like

This means that we want to make

TRPO - Trust-Region Policy Optimization

If we were to keep the KL-constraint in our objective instead of a soft ratio-clipping objective with PPO, then the formulation is different. This is called TRPO.

Our surrogate objective is now